Feelings and actions in Homer characters offer a wonderful and rich amount of clues as to the ancient Greek world’s moral values, religious creed and social custom and rituals. Nevertheless we usually tend to idealise the heroes and their acts, and we seldom actually contextualise the poems, a practice that sometimes may lead us to contradictory or fallacious interpretations of their behaviour. For instance: Odysseus is back to Ithaca after twenty years of (mis)adventurous wanderings, thanks to the help of Athena he is disguised as an old beggar and hosted in his own palace by his own (still unaware) wife and his accomplice son; yet there is no time at all to cherish his return: his first duty is to take back the control of his kingdom, his palace, his oikos and avenge himself. To restore his honour and take vengeance is his first and foremost aim. The occasion is given by the uninformed Penelope herself:

“Now when the fair lady reached the wooers, she stood by the door-post of the well-built hall, holding before her face her shining veil; and a faithful handmaid stood on either side of her. Then straightway she spoke among the wooers, and said: “Hear me, ye proud wooers, who have beset this house to eat and drink ever without end, since its master has long been gone, nor could you find any other plea to urge, save only as desiring to wed me and take me to wife. Nay, come now, ye wooers, since this is shown to be your prize. I will set before you the great bow of divine Odysseus, and whosoever shall most easily string the bow in his hands and shoot an arrow through all twelve axes, with him will I go, and forsake this house of my wedded life, a house most fair and filled with livelihood, which, methinks I shall ever remember even in my dreams.”

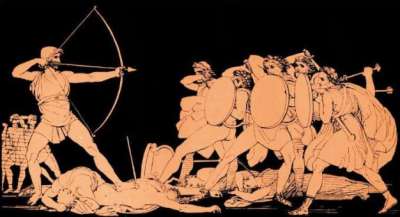

Odysseus awaits in a corner and observes each of the candidates’ failure, and finally asks for the permission to try; then allowed by the Queen, among the laughs and mockeries of the all the contenders, he grabs the bow and effortlessly aces the test. This is the moment of revelation and revenge: Telemachus in his shining bronze armour takes the stand by his father’s side and Odysseus, suddenly back to his young and strong himself, taking everyone by surprise kills first Antinous (with an arrow through his throat) and then one by one the whole 108 usurpers.

Now, some readers – and even some scholars – deem this violent vendetta rather excessive, especially considering the crimes committed by the pretenders were not that grave, even in those days. Furthermore it is worth to notice that among the 108 suitors-victims there are several quite different personalities with distinct aims and levels of participation to the felonies perpetrated by the bunch. Actually Homer refers to the suers quite always as a group, nonetheless, there are examples within and throughout the poem into which the Poet describes individuals by characterising either their specific evil disposition or their disagreement and/or dissociation with respect to some criminal decisions and ill-actions performed by the group.

There is no doubt that Antinous, their natural charismatic chief, was portrayed as the worst of them all, keenly taking advantage of the devastating situation in Ithaca and trying unsuccessfully to kill Telemachus:

“The wooers they straightway made to sit down and cease from their games; and among them spoke Antinous, son of Eupeithes, in displeasure; and with rage was his black heart wholly filled, and his eyes were like blazing fire. “Out upon him, verily a proud deed has been insolently brought to pass by Telemachus, even this journey, and we deemed that he would never see it accomplished. Forth in despite of all of us here the lad is gone without more ado, launching a ship, and choosing the best men in the land. He will begin by and by to be our bane; but to his own undoing may Zeus destroy his might before ever he reaches the measure of manhood. But come, give me a swift ship and twenty men, that I may watch in ambush for him as he passes in the strait between Ithaca and rugged Samos. Thus shall his voyaging in search of his father come to a sorry end.” So he spoke, and they all praised his words, and bade him act”.

Actually twice failing in his plot and yet eagerly inciting his companions:

“Then among them spoke Antinous, son of Eupeithes: “Lo, now, see how the gods have delivered this man from destruction. Day by day watchmen sat upon the windy heights, watch ever following watch, and at set of sun we never spent a night upon the shore, but sailing over the deep in our swift ship we waited for the bright Dawn, lying in wait for Telemachus, that we might take him and slay the man himself; howbeit meanwhile some god has brought him home. But, on our part, let us here devise for him a woeful death, even for Telemachus, and let him not escape from out our hands, for I deem that while he lives this work of ours will not prosper. For he is himself shrewd in counsel and in wisdom, and the people nowise show us favour any more. Nay, come, before he gathers the Achaeans to the place of assembly–for methinks he will in no wise be slow to act, but will be full of wrath, and rising up will declare among them all how that we contrived against him utter destruction, but did not catch him; and they will not praise us when they hear of our evil deeds. Beware, then, lest they work us some harm and drive us out from our country, and we come to the land of strangers. Nay, let us act first, and seize him in the field far from the city, or on the road; and his substance let us ourselves keep, and his wealth, dividing them fairly among us; though the house we would give to his mother to possess, and to him who weds her. Howbeit if this plan does not please you, but you choose rather that he should live and keep all the wealth of his fathers, let us not continue to devour his store of pleasant things as we gather together here, but let each man from his own hall woo her with his gifts and seek to win her; and she then would wed him who offers most, and who comes as her fated lord.”

But above all is he the very one who beats up Ulysses (while he was camouflaged as a ragged vagrant) the very morning of our hero’s revenge:

“…and Antinous waxed the more wroth at heart, and with an angry glance from beneath his brows spoke to him winged words: “Now verily, methinks, thou shalt no more go forth from the hall in seemly fashion, since thou dost even utter words of reviling.” So saying, he seized the footstool and flung it, and struck Odysseus on the base of the right shoulder, where it joins the back. But he stood firm as a rock, nor did the missile of Antinous make him reel; but he shook his head in silence, pondering evil in the deep of his heart.”

Eurymachus is another ill-character, he takes the command after Antinous’ death, but immediately afterwards he realises that there is no gateway, consequently he tries another strategy by admitting the serious offence he caused and offering his public apology by paying him back for the damages and his wrongdoing:

“many deeds of wanton folly in thy halls and many in the field…. but do thou spare the people that are thine own; and we will hereafter go about the land and get thee recompense for all that has been drunk and eaten in thy halls, and will bring each man for himself in requital the worth of twenty oxen, and pay thee back in bronze and gold until thy heart be warmed; but till then no one could blame thee that thou art wroth.”

Eurymachus’ proffer cannot be deemed totally inconsiderate by Ancient Greek standards, yet his cowardice is peer to his deceitfulness as he puts the entire blame on the just murdered – and until only a few minutes before comrade – Antinous:

“But he [Antinous] now lies dead, who was to blame for all, even Antinous; for it was he who set on foot these deeds, not so much through desire or need of the marriage, but with another purpose, which the son of Cronos did not bring to pass for him, that in the land of settled Ithaca he might himself be king, and might lie in wait for thy son and slay him”.

The deal – act of contrition and patrimonial indemnity – is brusquely refused by Odysseus:

“Eurymachus, not even if you should give me in requital all that your fathers left you, even all that you now have, and should add other wealth thereto from whence ye might, not even so would I henceforth stay my hands from slaying until the wooers had paid the full price of all their transgression. Now it lies before you to fight in open fight, or to flee, if any man may avoid death and the fates; but many a one, methinks, shall not escape from utter destruction.”

Thus the feral revenge takes place, no escape, no mercy, one by one the suitors are slain by a thunderous Odysseus:

“…Odysseus amid the bodies of the slain, all befouled with blood and filth, like a lion that comes from feeding on an ox of the farmstead, and all his breast and his cheeks on either side are stained with blood, and he is terrible to look upon..”.

What has been often remarked is that Odysseus unemotionally kills all of them, including Leiodes, their soothsayer who always sincerely dreaded their actions:

“But Leiodes rushed forward and clasped the knees of Odysseus, and made entreaty to him, and spoke winged words: “By thy knees I beseech thee, Odysseus, and do thou respect me and have pity. For I declare to thee that never yet have I wronged one of the women in thy halls by wanton word or deed; nay, I sought to check the other wooers, when any would do such deeds. But they would not hearken to me to withhold their hands from evil, wherefore through their wanton folly they have met a cruel doom. Yet I, the soothsayer among them, that have done no wrong, shall be laid low even as they; so true is it that there is no gratitude in aftertime for good deeds done.”.

And also shows no mercy for Amphinomus, an unprejudiced personage who had appeared wise also to Penelope’s eyes:

“He was the glorious son of the prince Nisus, son of Aretias, and he led the wooers who came from Dulichium, rich in wheat and in grass, and above all the others he pleased Penelope with his words, for he had an understanding heart.”

and had refused to participate in the plot for the assassination of Telemachus:

“Friends, I surely would not choose to kill Telemachus; a dread thing is it to slay one of royal stock…”

Thus Odysseus’ conduct may seem somewhat incongruous as he completely disregards the individual behaviour of the single members of the bunch and massacres indifferently each and everyone of them ignoring any of their attempts of justification and even any considerate appeal for mercy, including the one of Leiodes – regardless “deeds of wanton folly were hateful to him alone, and he was full of indignation at all the wooers”.

In reality in Homeric society revenge, justice and punishment are conceived, placed and administered at different levels. In Homer’s world vengeance takes no notice of behavioural choices taken by the offender: no matter if he was under pressure, or obeying an order or worse just following the stream while mingling within the crowd – which is the case. There is no consideration whatsoever as to the possible unequal conscience’s situations and single ethic circumstances within the members of the gang. Revenge has no concern for consciousness and culpability, willingness and motive: these concepts pertain to the justice’s sphere, which has really little to do with reprisal itself. In Homer, vendetta is a mere matter of honour – offended honour – and the only plausible reparations within this ancient themis and nomos framework are either the killing or the forgiveness. Nonetheless each and both determinations have no other reason to prevail than the offended pure will, without any possible reference to the circumstances, intentions and emotional participation that have accompanied the committed crime. Honour, if it has been offended, must be somehow compensated, in a form and in a way that can unquestionably restore the image, stature and status of the insulted king primarily within his own community and even in the outer world – he will incontestably decide his offenders’ atonement path.

Ultimately vendetta within the Homeric poems is purely a matter of regaining incontrovertibly the lost reputation and re-establishing social standing and political power and credibility above and within the community. Therefore, given the perpetrated and reiterated offences carried out against his realm, family, possessions and oikos in general, Odysseus – albeit certainly also blinded by his escalating rage – seems to have followed paradigmatically, and rather canonically, the ritual retaliation of mass hybris.