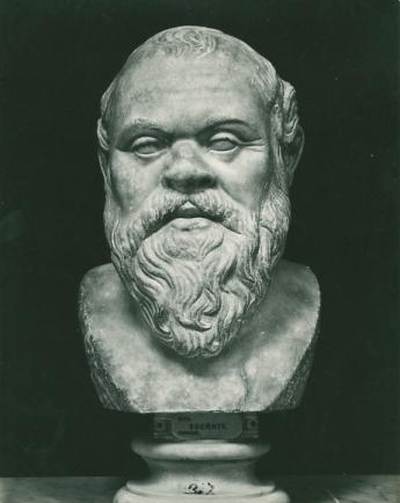

I have just this very instant completed reading “The Hemlock Cup”. Socrates, Athens and the Search for the Good Life, by Bettany Hughes a splendid portrait of a man, an extremely documented and detailed description of a society and an marvellous representation of an epoch.

I have greatly admired, perusing its pages, the endeavour and conscientiousness with which the author has assembled countless pieces of information of different nature and sources (historical, philological, literary, archaeological etc.) in order to converge towards a unexpectedly brilliant portrayal of the man considered the father of modern western thought.

In truth many events concerning Socrates’ existence are wrapped in a veil of uncertainty, thus compelling Ms. Hughes’ serious philological background unavoidably to prevail and as a consequence to consciously and frankly infer a few facts. Nevertheless the narration never lowers its rhythm, on the contrary: continuous chronicled references on Athenian daily life and actual allusions on museum and archaeological sites spur the imagination and the time-travel experience of any – even the one not initially enthusiast – reader.

It is also true that there are many Socrates’ scholars and biographers, which most likely have dissected any possible historical and philosophical aspect of Socrates’ life and death; yet the book offers an original and multifaceted portraiture of Socrates’ times and society enriched with indirect and sometimes anecdotal information about his shoddy demeanour and inquisitive attitude, and delivers us a closer view of the “human being” instead of the unreachable puzzling Greek philosopher.

Now I cannot refrain wondering a renown and yet recurrent paramount question: how could Athens, such a highly praised civilisation – probably the very incarnation of Western Golden Age – accuse and sentence to death its most prominent mind and eminent son? Athens, the cradle of the same philosophy which has dominated sciences, arts, politics and life at least until the Middle Age and still influences modern thought; the mother and model of democracy, implementing any possible device to involve and include as many citizens as possible in active political life and to avert bribery and enticement – and the eulogy could go on and on…

In this regard Alexis de Tocqueville in 1840 bluntly concluded that:

Athènes, avec son suffrage universel, n’était donc, après tout, qu’une république aristocratique où tous les nobles avaient un droit égal au gouvernement. [De la démocratie en Amérique, Tome Deuxième, Chap. XV]

More harshly George Bernanos, in 1942, thus accused the French collaborationists, considering that elite culpable of betraying the French loyal spirit and code of honour:

En parlant ainsi je me moque de scandaliser les esprits faibles qui opposent aux réalités des mots déjà dangereusement vidés de leur substance, comme par exemple celui de Démocratie

La Démocratie est la forme politique du Capitalisme, dans le même sens que l’âme est la Forme du corps selon Aristote, ou son Idée, selon Spinoza. [Lettre aux Anglais, Atlantica editora, Rio de Janeiro 1942].

But way before XIX or XX century even Plato, already in his days – not too far from those of the death of his mentor – identifies the very root of the question, when he allows his fictional Socrates to unveil it by quoting an ironical parody of the legendary self-celebrating Pericles’ epitaph for the dead soldiers of the Peloponnesian War (in Plato’s dialogue fictitiously ghost-written by Aspasia, Pericles’ mistress):

…ἐπιμνησθῆναι. πολιτεία γὰρ τροφὴ ἀνθρώπων ἐστίν, καλὴ μὲν ἀγαθῶν, ἡ δὲ ἐναντία κακῶν. ὡς οὖν ἐν καλῇ πολιτείᾳ ἐτράφησαν οἱ πρόσθεν ἡμῶν, ἀναγκαῖον δηλῶσαι, δι’ ἣν δὴ κἀκεῖνοι ἀγαθοὶ καὶ οἱ νῦν εἰσιν, ὧν οἵδε τυγχάνουσιν ὄντες οἱ τετελευτηκότες. ἡ γὰρ αὐτὴ πολιτεία καὶ τότε ἦν καὶ νῦν, ἀριστοκρατία, ἐν ᾗ νῦν τε πολιτευόμεθα καὶ τὸν ἀεὶ χρόνον ἐξ ἐκείνου ὡς τὰ πολλά. καλεῖ δὲ ὁ μὲν αὐτὴν [d] δημοκρατίαν, ὁ δὲ ἄλλο, ᾧ ἂν χαίρῃ, ἔστι δὲ τῇ ἀληθείᾳ μετ’ εὐδοξίας πλήθους ἀριστοκρατία. βασιλῆς μὲν γὰρ ἀεὶ ἡμῖν εἰσιν· οὗτοι δὲ τοτὲ μὲν ἐκ γένους, τοτὲ δὲ αἱρετοί· ἐγκρατὲς δὲ τῆς πόλεως τὰ πολλὰ τὸ πλῆθος, τὰς δὲ ἀρχὰς δίδωσι καὶ κράτος τοῖς ἀεὶ δόξασιν ἀρίστοις εἶναι, καὶ οὔτε ἀσθενείᾳ οὔτε πενίᾳ οὔτ’ ἀγνωσίᾳ πατέρων ἀπελήλαται οὐδεὶς οὐδὲ τοῖς ἐναντίοις τετίμηται, ὥσπερ ἐν ἄλλαις πόλεσιν, ἀλλὰ εἷς ὅρος, ὁ δόξας σοφὸς ἢ ἀγαθὸς εἶναι κρατεῖ καὶ ἄρχει. [ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ ΜΕΝΕΞΕΝΟΣ, 238, c,d]

For a polity is a thing which nurtures men, good men when it is noble, bad men when it is base. It is necessary, then, to demonstrate that the polity wherein our forefathers were nurtured was a noble one, such as caused goodness not only in them but also in their descendants of the present age, amongst whom we number these men who are fallen. For it is the same polity which existed then and exists now, under which polity we are living now and have been living ever since that age with hardly a break. One man calls it “democracy,” another man, according to his fancy, gives it some other name; but it is, in very truth, [d] an “aristocracy” backed by popular approbation. Kings we always have; but these are at one time hereditary, at another selected by vote. And while the most part of civic affairs are in the control of the populace, they hand over the posts of government and the power to those who from time to time are deemed to be the best men; and no man is debarred by his weakness or poverty or by the obscurity of his parentage, or promoted because of the opposite qualities, as is the case in other States. On the contrary, the one principle of selection is this: the man that is deemed to be wise or good rules and governs.

Thus the enthusiasts of Athenian democracy have often failed, purposely or naively, to envisage the clearly distinguishable components and facets of an oligarchy of very few wealthy families, of which the rest of citizens (the vast majority, poor and illiterate) were easy preys; a sect of professional politicians/orators ruling the city slyly and untouched; an economic elite purporting an actual form of modern proto-imperialism over the Aegean Sea by means of a self-celebrating fame, violence and taxation to the benefit of a self-preserving authority.

It appears that the unconditional laudator temporis acti approach towards ancient Athens tends, still nowadays, to disregard the side effects even of the best democracy: its step-sister demagogy – perhaps the true responsible of Socrates’ death.