In Greek ancient history 406 B.C. is remembered for the battle of Arginusae and the consequent fretly taken death sentence issued against six Athenian generals who, albeit having won the combat, did not rescue the crews of some ships hit during the fight – allegedly because of the adverse weather conditions; a brutal and unreasonable episode that symbolises a remarkable change, the descending fate of the Attic overestimated supremacy and consequently the early days of the sunset of the ancient Greek civilisation. In my opinion though, the year 406 B.C. coincidentally marks one of the most important events of antiquity, impacting the future development of the western thought, as both Aeschylus and Euripides died and with them the Attic tragedy.

The death of Euripides, a true and profound thinker, an incredibly deep analyser of human nature, capable to discover the anxieties of man’s soul, an acute and often obscure witness of the changing times, coincides perhaps with the beginning of our own era. The dawn of a new function attributed to drama – and, maybe, art in general – the birth of a new theatre conceived and considered as pure aesthetic experience, just like a seeming Spiegel of life. What is represented on stage is not aiming at any profound touching, conversion or reflection but to mere pleasure: art as aesthetic per se.

Yet in 405 B.C. Euripides’ echo still lingers on his contemporaries in a tragedy represented abroad, in Amphipolis, where he had found refuge under the protection of King Archelaus: Bacchae.

Bacchae is to be considered the very last message of an exhausted and old Euripides, misapprehended and undervalued by his generation, and discomforted by the events he had witnessed and by being misunderstood when he so generously had tried to give us clues to interpret our human condition, to enlighten us by tossing us a key to endure the sense of life. Euripides acknowledges the precariousness and uncertainty of being and firmly admonishes all those that are either unaware or disregard their status of being human and consequently frail and not at all faultless. He condemns the spreading excess of self-confidence of mankind and consequently discourages those ambitions that overestimate human abilities, both as individuals and even worse when gathered in a crowd; the same crowd that had sentenced to death the generals of Arginusae, and the very same assembly that will shortly afterwards sentence to death Socrates.

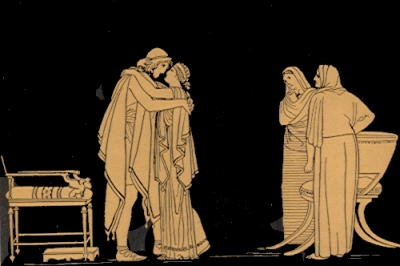

In Bacchae, Dionysus, arrives in Thebe in disguise, in order to affirm his questioned status of God and to prevent the sacrilegious abolition his rituals and ceremonies:

Behold, God’s Son is come unto this land

Of heaven’s hot splendour lit to life, when she

Of Thebes, even I, Dionysus, whom the brand

Who bore me, Cadmus’ daughter Semele,

Died here. So, changed in shape from God to man,

I walk again by Dirce’s streams and scan

Ismenus’ shore. There by the castle side

I see her place, the Tomb of the Lightning’s Bride,

The wreck of smouldering chambers, and the great

Faint wreaths of fire undying–as the hate

Dies not, that Hera held for Semele.

Dionysus allows himself to be captured and chained by King Pentheus who is determined to stop the God’s lascivious cult in his πολις, notwithstanding the admonishing wise words of Teiresias, that sounds like a preach coming from Euripides himself:

ὅταν λάβῃ τις τῶν λόγων ἀνὴρ σοφὸς

καλὰς ἀφορμάς, οὐ μέγ᾽ ἔργον εὖ λέγειν·

σὺ δ᾽ εὔτροχον μὲν γλῶσσαν ὡς φρονῶν ἔχεις,

ἐν τοῖς λόγοισι δ᾽ οὐκ ἔνεισί σοι φρένες.

θράσει δὲ δυνατὸς καὶ λέγειν οἷός τ᾽ ἀνὴρ

κακὸς πολίτης γίγνεται νοῦν οὐκ ἔχων.

[Good words my son, come easily, when he

That speaks is wise, and speaks but for the right.

Else come they never! Swift are thine, and bright

As though with thought, yet have no thought at all]

Pentheus saturated by his over-confidence also doubts about Dionysus divine origins, and therefore he blasphemously dares to ill-treat him and at times he even mocks him:

Marry, a fair shape for a woman’s eye,

Sir stranger! And thou seek’st no more, I ween!

Long curls, withal! That shows thou ne’er hast been

A wrestler!–down both cheeks so softly tossed

And winsome! And a white skin! It hath cost

Thee pains, to please thy damsels with this white

And red of cheeks that never face the light!

(omissis…)

First, shear that delicate curl that dangles there.

The punishment of Pentheus’ arrogance and overriding self-confidence undergoes a long gestation, a stratagem used surely to enhance the taste of vengeance of Dionysus – who plays like the cat with the mouse – but mainly this ploy is used by the author to divulge how useless can be any human design and planning if one ponders and realises how many are the uncontrollable variables that characterise any event and action in our life. To add drama Dionysus prefers to have Pentheus own mother, Agave, to unintentionally perform his revenge: during the Baccahe ritual the God induces Pentheus to disguise himself in woman attire and spy the forbidden lubricous ceremony: the poor semi-unconscious mother slays Pentheus thinking he is a lion and triumphantly will show her son’s head. Dionysus will lead the epilogue explaining and stating his supremacy and how feeble and disillusioned humans can be.

Wise words are spoken by Euripides who borrows again old Teiresias’ voice and perfectly stigmatised the human limits that should never be forgotten:

οὐδὲν σοφιζόμεσθα τοῖσι δαίμοσιν.

πατρίους παραδοχάς, ἅς θ᾽ ὁμήλικας χρόνῳ

κεκτήμεθ᾽, οὐδεὶς αὐτὰ καταβαλεῖ λόγος,

οὐδ᾽ εἰ δι᾽ ἄκρων τὸ σοφὸν ηὕρηται φρενῶν.

ἐρεῖ τις ὡς τὸ γῆρας οὐκ αἰσχύνομαι,

μέλλων χορεύειν κρᾶτα κισσώσας ἐμόν;

οὐ γὰρ διῄρηχ᾽ ὁ θεός, οὔτε τὸν νέον

εἰ χρὴ χορεύειν οὔτε τὸν γεραίτερον,

ἀλλ᾽ ἐξ ἁπάντων βούλεται τιμὰς ἔχειν

κοινάς, διαριθμῶν δ᾽ οὐδέν᾽ αὔξεσθαι θέλει

[Or prove our wit on Heaven’s high mysteries?

Not thou and I! That heritage sublime

Our sires have left us, wisdom old as time,

No word of man, how deep soe’er his thought

And won of subtlest toil, may bring to naught.

Aye, men will rail that I forgot my years,

To dance and wreath with ivy these white hairs;

What recks it? Seeing the God no line hath told

To mark what man shall dance, or young or old;

But craves his honours from mortality

All, no man marked apart; and great shall be!]

Thus Euripides opens the gates to the beginning of a rather inglorious age – which perhaps is still ours –where actual values, sense of balance and true dimensions have become inhuman, out of reach, and steady refuge in the past cannot be answer. The unleashed overconfidence in human possibilities is of course the key of progress and has undoubtedly brought many technical and medical achievements, nevertheless it is undeniable that has also contaminated the human relationship with the environment and continuously impacts several – if not all – the actual aspects that pertain to the sense of living itself. Euripides unquestionably performed a comprehensive analysis and achieved a bright and lucid precocious diagnosis of both the essence and the discomforts of being, but unfortunately he left us without any therapy…