Alexander the Great, the Macedonian, grand general and irresistible conqueror, shrewd and charismatic, dissolute and merciless: altogether one of the most contradictorily impressive characters of the entire ancient world and founder of one of the largest empires of history whose expansion ranged from the Balkans to Punjab! Further to the kind enquiry of two of my most affectionate readers, here are some abstracts of my findings on Alexander’s two years in India – throughout the reports of the ancient texts.

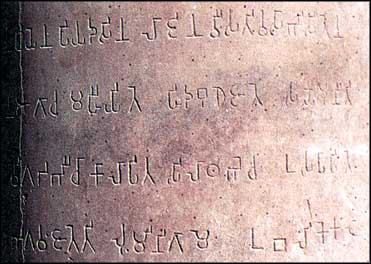

In the summer of 327 B.C. Alexander organised a new army which counted almost 120,000 soldiers: mainly Macedonians plus Egyptians and Phoenicians sailors (these latter were indispensable to sail along the river Indus); besides the Macedonians were barely sufficient for his war-campaign as he – moving on with his victories – needed also to establish political structures and organise military-bureaucratic infrastructures on the newly conquered territories. Thus, according to Lucius Flavius Arrianus (Arrian), Alexander crossed the river Indus from Hund and reached Taxila, just across the Hindu Kush – Καύκασος Ινδικός, where the king Omphis (also known as Taxiles) yielded himself:

“Alexander laid a bridge over the river Indus… when Alexander had crossed to the other side of the river Indus, he again offered sacrifice there, according to his custom. Then starting from the Indus, he arrived at Taxila, a large and prosperous city, in fact the largest of those situated between the rivers Indus and Hydaspes. He was received in a friendly manner by Taxiles, the governor of the city, and by the Indians of that place; and he added to their territory as much of the adjacent Country as they asked for.”

Taxiles also asked him for help against King Porus (or Raja Puru) of Pauravaa, between the rivers Hydaspes and the Acesines (Jhelum and the Chenab) in the Punjab and his ally the King of Kashmir Abisares-Αβισαρης (or Abhisara or Embisarus) whose reign was behind the river Hydaspes and his dominions extending to Hyphasis (nearby the present Lahore), who were together trying to conquer the whole of Punjab. Thus Alexander had made his first Indian ally, as Plutarch reports:

“Taxiles, we are told, had a realm in India as large as Egypt, with good pasturage, too, and in the highest degree productive of beautiful fruits. He was also a wise man in his way, and after he had greeted Alexander, said: “Why must we war and fight with one another, Alexander, if thou art not come to rob us of water or of necessary sustenance, the only things for which men of sense are obliged to fight obstinately? As for other wealth and possessions, so-called, if I am thy superior therein, I am ready to confer favours; but if thine inferior, I will not object to thanking you for favours conferred.” At this Alexander was delighted, and clasping the king’s hand, said: “Canst thou think, pray, that after such words of kindness our interview is to end without a battle? Nay, thou shalt not get the better of me; for I will contend against thee and fight to the last with my favours, that thou mayest not surpass me in generosity.” So, after receiving many gifts and giving many more, at last he lavished upon him a thousand talents in coined money. This conduct greatly vexed Alexander’s friends, but it made many of the Barbarians look upon him more kindly”.

During his stay in Taxila Alexander also was able to meet for the first time the famous Indian philosophers: the Gymnosophists, (Darshanas) and the Brahmins priests which seriously tried to endanger his plans and strategies as they both pushed cities and citizens against the foreign conqueror. He brutally reacted to this entanglement…:

“The philosophers, too, no less than the [Indian] mercenaries, gave him trouble, by abusing those of the native princes who attached themselves to his cause, and by inciting the free peoples to revolt. He therefore took many of these also and hanged them.”

Some other philosophers were more fortunate as Plutarchus reports:

“He captured ten of the Gymnosophists who had done most to get Sabbas to revolt, and had made the most trouble for the Macedonians. These philosophers were reputed to be clever and concise in answering questions, and Alexander therefore put difficult questions to them, declaring that he would put to death him who first made an incorrect answer.”

Alexander then showed even more curiosity for these ascetics and eagerly wanted to meet them, something he tried with alternate success…:

“These philosophers, then, he dismissed with gifts; but to those who were in the highest repute and lived quietly by themselves he sent Onesicritus, asking them to pay him a visit. Now, Onesicritus was a philosopher of the school of Diogenes the Cynic. And he tells us that Calanus very harshly and insolently bade him strip off his tunic and listen naked to what he had to say, otherwise he would not converse with him, not even if he came from Zeus; but he says that Dandamis was gentler, and that after hearing fully about Socrates, Pythagoras, and Diogenes, he remarked that the men appeared to him to have been of good natural parts but to have passed their lives in too much awe of the laws. Others, however, say that the only words uttered by Dandamis were these: “Why did Alexander make such a long journey hither?”

Plutarch says that Calanus eventually came to better terms and met Alexander, although his meeting ended with a wise suggestion that nonetheless incorporated a sinister presage…:

“Calanus, nevertheless, was persuaded by Taxiles to pay a visit to Alexander. His real name was Sphines, but because he greeted those whom he met with “Cale,” the Indian word of salutation, the Greeks called him Calanus. It was Calanus, as we are told, who laid before Alexander the famous illustration of government. It was this. He threw down upon the ground a dry and shrivelled hide, and set his foot upon the outer edge of it; the hide was pressed down in one place, but rose up in others. He went all round the hide and showed that this was the result wherever he pressed the edge down, and then at last he stood in the middle of it, and lo! it was all held down firm and still. The similitude was designed to show that Alexander ought to put most constraint upon the middle of his empire and not wander far away from it.”

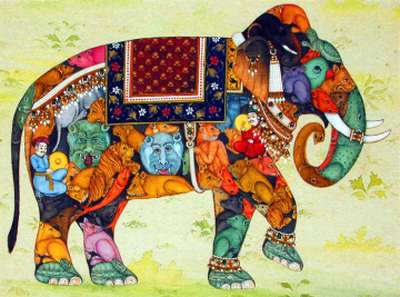

Thus according to Arrian in April-May 326 B.C. while king Abisares had sent his emissary to surrender without fighting, king Porus intended to contrast Alexander and was waiting to fight him with his army and 120 elephants across the river Hydaspes. A violent and sanguinary battle took place, with minor loss on Alexander’s army, while the Indians were severely defeated and both soldiers and elephants dispersed on the battlefield:

“Porus, with the whole of his army, was on the other side of that river, having determined either to prevent him from making the passage, or to attack him while crossing…. Alexander took the forces which he had when he arrived at Taxila, and the 5,000 Indians under the command of Taxiles and the chiefs of that district, and marched towards the same river… of the Indians little short of 20,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry were killed in this battle. All their chariots were broken to pieces; and two sons of Porus were slain”.

Even King Porus fought bravely and was wounded:

“Porus, who exhibited great talent in the battle, performing the deeds not only of a general but also of a valiant soldier… but at last, having received a wound on the right shoulder, which part of his body alone was unprotected during the battle, he wheeled round”

When Alexander met his imprisoned enemy: Porus, he was impressed by the courage and the charisma of his enemy. According to the dialogue Arrian has reported he treated him in a knightly manner and made him his new ally:

“Alexander… admired his [Porus] handsome figure and his stature, which reached somewhat above five cubits. He was also surprised that he did not seem to be cowed in spirit, but advanced to meet him as one brave man would meet another brave man, after having gallantly struggled in defence of his own kingdom against another king. Then indeed Alexander was the first to speak, bidding him say what treatment he would like to receive. The story goes that Porus replied: “Treat me, O Alexander, in a kingly way !“ Alexander being pleased at the expression, said : “For my own sake, O Porus, thou shalt be thus treated; but for thy own sake do thou demand what is pleasing to thee!” But Porus said that everything was included in that. Alexander, being still more pleased at this remark, not only granted him the rule over his own Indians, but also added another country to that which he had before, of larger extent than the former.’ Thus he treated the brave man in a kingly way, and from that time found him faithful in all things.”

Porus proposed Alexander to fight on his Eastern borders against the Nanda dynasty who ruled the kingdom of Magadha nearby Patliputra (nowadays Patna); the Macedonian soldiers started the march, nonetheless once they reached the river Hyphasis they refused to go any further as they wanted to go back home. Alexander, although reluctantly, adhered to their request and, as Diodorus Siculus reports, after having built 12 enormous altars to the Greek Pantheon put the expedition to an end.

“He decided thus to interrupt his campaign at this point, and in order to mark his limits he first of all erected altars of the twelve gods each fifty cubits high…”.

Actually the return would have revealed not as easy as he could have foreseen, as he had to split the army: some garrisons followed the banks of the Indus, others sailed along the river itself, others were exploring the ocean coasts of Belucistan (or Balochistan) and the Persian Gulf.

However the great triumph of Alexander’s warfare skills as well as the magnitude of his empire, though ephemeral, have been vastly celebrated along the centuries, and perhaps this passage from Quintus Curtius Rufus best synthesises the enthusiasm and spirit of victory and winners on their way back home:

“Iam nihil gloriae deesse; nihil obstare virtuti, sine ullo Martis discrimine, sine sanguine orbem terrae ab illis capi.”

[Now nothing was amiss to their glory; nothing could stop their courage: without fighting, without bloodshed they were the masters of the whole world.]

not quite as moving as – so antithetically, though – Joseph Roth’s description of the deep sadness and exhaustion accompanying the return to Vienna (on a sad 1918 Christmas Eve) of one of the victi, discomfited of the Great War:

“The armed bayonets seemed not at all real, the rifles where loosely hanging askew on the soldiers’ shoulders. It was like they wanted to sleep, the guns, tired of four years of shootings. I was not the least surprised if none of the soldiers saluted me, my stripped cap, my stripped jacket’s collar did not impose any obligation on anyone. Yet I did not rebel. It was only painful. It was the end.”