Since the ninth century B.C. the Greeks from the continent, Aegean Islands and Ionia (present Turkey West coast), following the same Mycenaean routes, resumed moving west and founding new colonies in Sicily and in the South of Italy. These early colonies, within a century multiplied all over the Western Mediterranean reaching Sardinia, Corsica, France and the Iberian Peninsula.

Most certainly cities such as Syracuse (now Siracusa), Massalia (today Marseille), Akragas (now Agrigento), Taras (today Taranto), Nicea (now Nice), Neapolis (today Napoli), Emporion (now Ampurias), are widely renown as having very old Greek roots, nonetheless the oldest Greek colony is a small island in the Tyrrhenian Sea: Pithekussa.

Is here that in the beginning of the eighth century B.C. the early settlers came and founded initially an emporion and then a real colony. According to Strabo’s Geography these sailors and merchants came originally from both the two main poleij of the island of Euboea: Chalcis and Eretria as they found good soil and also gold mines on the island. The former characteristic is true belonging the island to an active volcanic area, the latter is to be considered a legend, probably sort of propaganda to enhance the number of settlers, or simply to magnify the gestae of the early settlers when sending news to their hometown. Actually, the settlers found this location suitable being its size large enough to sustain a community as well as not too wide to be defended.

Having been founded in cooperation by these two poleij is a very useful detail when trying to date the colonisation, because these two πολεις became enemies in the end of the eighth century B.C. and fought a long lasting war (Lelantine War) which gave no significant success to Chalcis and destroyed Eretria: consequently this joint colonisation project must have been planned and taken place before the Lelantine War.

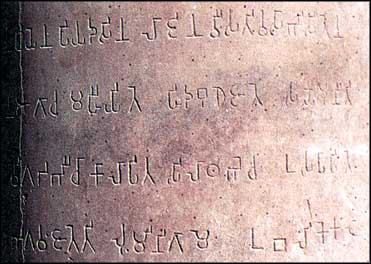

Archaeological evidence corroborates this dating, as a ceramic cup found in an eighth century B.C. tomb bears an extraordinary inscription:

The cup of Nestor may have been certainly pleasant to drink from,

but who drinks from this cup immediately will be taken by the desire of Aphrodite by the splendid tiara

This is the oldest epigraph ever found in the Western Mediterranean Greek colonisation area, and both its syntax and style are quite sophisticated and mature for its age. The irony of the inscription (hinting to some aphrodisiac powers of the beverages it could have contained) and the literary reference to a precise detail of a minor Iliad character Nestor King of Πυλος confirm the degree of erudition of some island’s inhabitants in the eighth century who, by then, could not have been just sailors using it as a stepping stone. Soon the settlers expanded to another smaller neighbour island, Aenaria, just between Pithekussa and the continent.

The island was naturally endowed with argillaceous soil, which in those days was a very important resource for the island’s ceramic manufacturers: lots of pottery made on Pithekussa was exported to the continental Italy, especially in Etruscan areas. Moreover, this was probably the etymology of the island’s name: pithos (vase); although according to another – minor, though – etymology the island’s name would come from pithekos (monkey).

The settlers lived in harmony with the indigenous population – the Ausones – as they were good farmers and bartered their produces with any kind of utensil that the Greeks were so skilled at producing. The artisans of Pithekussa were also famous goldsmiths and worked the iron imported from the Etruscan Tuscany.

Later the population left the island to move to the main land. Actually this was the most common way the Greek settlers used to move along their colonial travels: they used to find little islands nearby the continent and settle down, then once they had gained enough knowledge of the site and its mainland surroundings, made friends with – or defeated – the indigenous population, they moved to the continent that could offer a wider and richer area for cultivation (mainly cereals, olive and vine) and sheep farming. Also many artisans and ceramists moved to the continent and opened shops even in many Etruscan areas.

Thus the barycentre of the Euboean colonisation shifted a few miles to the mainland and namely to Κυμη (Cuma), that is considered officially the first colony of the Western Greek colonisation, as Pithekussa and Aenaria had a relatively short life as settlements and did not became a real polij. According to Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita, Cuma then founded more cities, Δικαιαρχαιας (Dichearchias), Παλεπολις and Νεαπολις.

In present days Pithekussa is named Ischia: a renowned tourist destination in the Gulf of Naples, Aenaria (now Procida) is a small fisherman island recently developing some tourism, Cuma still retains its Greek name and belongs, together with Dichearchias (now Pozzuoli) to the outskirts of Naples the metropolis that lies and where Palepolis and Neapolis used to be.