Due to some strange reason, which I am still attempting to gauge, a noteworthy number of my girlfriends (meaning, naturally, female friends of mine…) indulge me with the honour of sharing their sentimental plights and grace me by soliciting my opinion and advice applicable to their love relationships. I find this peculiar circumstance both gratifying and worrisome at the same time: I do not deem myself the Antonio de Nebrija of love affairs as, because of my age and my average love life, I cannot possibly be particularly qualified to steer anyone’s assessment and decision within the highly intricate romantic field.

Nevertheless I confess that many have been so far the cases submitted to my wise estimation and in reference to which I have been warmly requested to express my reflections and contribute with my discernment; and pretty various have been the knotty, dire and thorny situations I have had the chance to encounter and hear, as well as quite diverse and well assorted is the gallery of their unfortunate female protagonists: being them such a greatly heterogeneous set of samples in so far as temperament, character, age and background are concerned. Yet, in conscience I believe it would be by all means accurate to affirm that – regardless the different state of affairs and scenarios – the main sources of their pains and grief can all be easily clustered under a sole and main paramount question: “Why do I always pick the wrong man?”

In truth I have some knowledge of stochastic analysis and therefore I cannot scientifically admit that this planet could be largely – if not solely – populated by Bireno’s comrades and poor Olimpia’s companions, and thus it cannot possibly be acceptable that each and every damsel’s customary doom is to awake stranded on a desert beach on an island off Scotland finding out her loved one is gone away to Zealand as Ludovico Ariosto narrates:

“Né desta né dormendo, ella la mano

per Bireno abbracciar stese, ma invano.

Nessuno truova: a sé la man ritira:

di nuovo tenta, e pur nessuno truova.

Di qua l’un braccio, e di là l’altro gira;

or l’una, or l’altra gamba; e nulla giova…

…Corre di nuovo in su l’estrema sabbia,

e ruota il capo e sparge all’aria il crine;

e sembra forsennata, e ch’adosso abbia

non un demonio sol, ma le decine;

o, qual Ecuba, sia conversa in rabbia,

vistosi morto Polidoro al fine.

Or si ferma s’un sasso, e guarda il mare;

né men d’un vero sasso, un sasso pare.”

[Between wake and sleep her arm she gently moves

Bireno to embrace whom she so love, but in vain.

There’s no-one there; her hand again she tends;

She gropes once more; then, finding no-one still,

First one and the another leg extends,

This way and that, but all to no avail…

… Again she runs along the sandy shore,

Hither and thither; not Olimpia

She seems, but some mad creature by a score

Of demons driven, or like Hecuba,

A prey to frenzy when her Polydore

She found there lying dead; and then afar

Olimpia gazes seawards, like a stock,

Standing so still a rock upon a rock.”]

Clearly I am fully aware that scoundrels, gold-diggers, social-climbers and adventure-seekers of both sexes do actually exist and do sadly roam around; yet this is to be considered more the exception rather than the rule; besides this is not the case I am hereby contemplating. With unambiguous reference to sound and morally unbiased relations – and thus excluding shallow petty Don Giovanni and hysterical post-feminists women – I am indeed more inclined to believe that, in spite of the spreading higher level of education and of the conquests of social emancipation, still misconceptions, misconstructions, miscommunication and misunderstandings tend inexorably to lead and send astray too many interactions between good-natured and well-intentioned men and women.

Among the vast number of hardly comprehensible causes I am firmly convinced that, regardless the numerous possibilities, occasions and instruments of social contact and dialogue, there is still a great deal of authentic solitude, diffidence and seclusion around. A circumstance that affects the concrete perception and vision of real life, stimulates dangerous over-speculations, encourages treacherous idealisations, inspires highly judgmental attitudes, rises expectations up to an unrealistic sphere and altogether consequently enfolds into a bundle of stiff preconceptions the entire framework of human relations and easily leads to the frustrations of Gautier’s chevalier d’Albert:

“Cela tient peut-être à ce que je vis beaucoup avec moi-même, et que les plus petits détails dans une vie aussi monotone que la mienne prennent une trop grande importance. Je m’écoute trop vivre et penser : j’entends le battement de mes artères, les pulsations de mon cœur ; je dégage, à force d’attention, mes idées les plus insaisissables de la vapeur trouble où elles flottaient et je leur donne un corps. – Si j’agissais davantage, je n’apercevrais pas toutes ces petites choses, et je n’aurais pas le temps de regarder mon âme au microscope, comme je le fais toute la journée. Le bruit de l’action ferait envoler cet essaim de pensées oisives qui voltigent dans ma tête et m’étourdissent du bourdonnement de leurs ailes : au lieu de poursuivre des fantômes, je me colletterais avec des réalités ; je ne demanderais aux femmes que ce qu’elles peuvent donner : – du plaisir, – et je ne chercherais pas à embrasser je ne sais quelle fantastique idéalité parée de nuageuses perfections. – Cette tension acharnée de l’œil de mon âme vers un objet invisible m’a faussé la vue. Je ne sais pas voir ce qui est, à force d’avoir regardé ce qui n’est pas, et mon œil si subtil pour l’idéal est tout à fait myope dans la réalité… Peut-être aussi que, ne trouvant rien en ce monde qui soit digne de mon amour, je finirai par m’y adorer moi-même, comme feu Narcisse d’égoïste mémoire. ”

Even though this sort of unconsciously secluded sentimental life, this άβιος βίος is a genderless widely diffused state nowadays, women who truly believe to be ill-fated because they chance to date always and only wrong partners are most likely the very same individuals who tend to be prey of this perilous enmeshment and thus somehow they are more prone in driving away any – even earnest – pursuer:

“Les honnêtes femmes, même lorsqu’elles le sont moins, ont une façon rechignée et dédaigneuse qui m’est parfaitement insupportable. Elles vous ont l’air toujours prêtes à sonner et à vous faire jeter à la porte par leurs laquais ; – et il me semble, en vérité, qu’un homme qui prend la peine de faire la cour à une femme (ce qui n’est pas déjà aussi agréable qu’on veut le croire) ne mérite pas d’être regardé de cette manière-là.”

Without any shade of doubt it is far from my aim to recommend that an unadorned and straightforward love declaration (or rather a business proposition…) such as the one declaimed by Cervantes’ personage of Doña Estefanía de Caicedo would have miraculous effects on anyone’s love twinges:

”Señor alférez Campuzano, simplicidad sería si yo quisiese venderme a vuesa merced por santa: pecadora he sido, y aun ahora lo soy, pero no de manera que los vecinos me murmuren ni los apartados me noten. Ni de mis padres ni de otro pariente heredé hacienda alguna, y con todo esto vale el menaje de mi casa, bien validos, dos mil y quinientos escudos; y éstos en cosas que, puestas en almoneda, lo que se tardare en ponellas se tardará en convertirse en dineros. Con esta hacienda busco marido a quien entregarme y a quien tener obediencia; a quien, juntamente con la enmienda de mi vida, le entregaré una increíble solicitud de regalarle y servirle; porque no tiene príncipe cocinero más goloso ni que mejor sepa dar el punto a los guisados que le sé dar yo, cuando, mostrando ser casera, me quiero poner a ello. Sé ser mayordomo en casa, moza en la cocina y señora en la sala; en efeto, sé mandar y sé hacer que me obedezcan. No desperdicio nada y allego mucho; mi real no vale menos, sino mucho más cuando se gasta por mi orden. La ropa blanca que tengo, que es mucha y muy buena, no se sacó de tiendas ni lenceros; estos pulgares y los de mis criadas la hilaron; y si pudiera tejerse en casa, se tejiera. Digo estas alabanzas mías porque no acarrean vituperio cuando es forzosa la necesidad de decirlas. Finalmente, quiero decir que yo busco marido que me ampare, me mande y me honre, y no galán que me sirva y me vitupere. Si vuesa merced gustare de aceptar la prenda que se le ofrece, aquí estoy moliente y corriente, sujeta a todo aquello que vuesa merced ordenare, sin andar en venta, que es lo mismo andar en lenguas de casamenteros, y no hay ninguno tan bueno para concertar el todo como las mismas partes”.

Nonetheless if women would include within their seduction weapons together with mascara, lip-gloss and stay-ups a sound dose of wise lenience and prudent forbearance, accompanied by a sensible non-over-judgemental attitude in accepting their partners for what they are and truly value the efforts they endeavour to please them – this could become quite a clever and judicious move. As brilliantly stated in Hugo von Hoffmannsthal’s “Der Schwierige” within an interesting dialogue between a rather dreary brother and his witty sister:

HANS KARL BÜHL – My dear, I take my hat off to your energetic resolutions, but men are not this simple, thank God!

CRESCENCE BÜHL – My dear, men – thank God! – are simple; if women take them with simplicity.

As to the final outcome: well, let us all rely on an old master – Heraclitus:

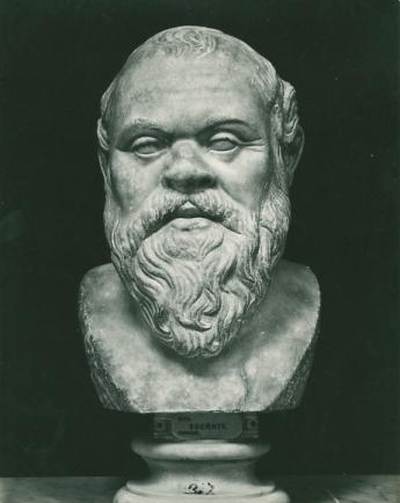

“ἐὰν μὴ ἔλπηται͵ ἀνέλπιστον οὐκ ἐξευρήσει͵ ἀνεξερεύνητον ἐὸν καὶ ἄπορον”

“If you do not hope, you will not find that which is not hoped for; since it is difficult to discover and impossible to attain.”